A Forgotten and Forbidden 19th Century American Love Story

On this Valentine's Day, I honor a long-forgotten and controversial couple, Mr and Mrs Smith. Unfair accusations have plagued them for 150 years.

(Agnes Gilkerson-Smith)

On this Valentine’s Day, let’s take a break from Covid, the deadly Pharma injections and the rise of repressive regimes. Let’s remember why we fight for human rights, freedom and justice. We do so in the name of all that’s Good, Noble and True, so that these lofty ideals may prosper and give hope to current and future generations.

One day last spring, while driving in the countryside of south New Jersey, serendipity led me to a remote place that 150 years ago was the scene of a beautiful and controversial love story. On that Sunday morning I dropped my daughter off at her gymnastics competition in the town of Mt. Holly. Due to Covid restrictions, parents weren't allowed to enter the complex, so I drove aimlessly about, trying to kill time.

I made a ‘wrong’ turn, and couldn’t turn back on the narrow country backroad. I felt compelled to drive onward, through the forest and fields, until I came to a lovely and grand 19th century estate. Smithville. Little did I suspect that this picturesque mansion held a forgotten secret. Here’s the story that I found… the true story of Mr and Mrs Smith, and their love that extends beyond the grave.

Not surprisingly, like any great love story, there’s a nefarious antagonist — and once again, not surprisingly, that antagonist is aided by a warped and twisted media that lied in the 19th century about Mr and Mrs Smith, and which today still spreads falsehoods through deceptive innuendo and deliberate omission of key facts.

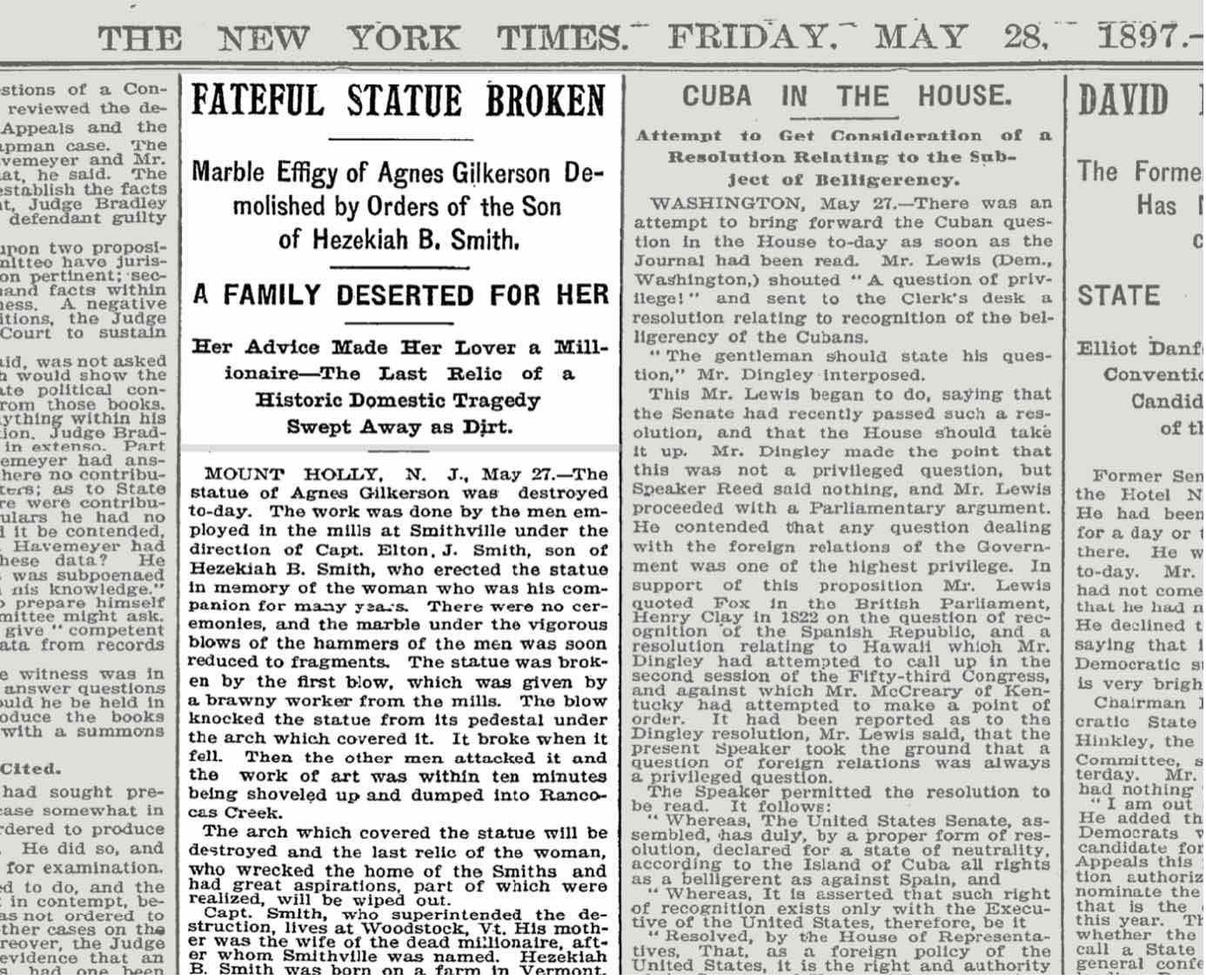

While the couple lived happily together in the 1860s and 1870s, I first need to mention an article published on May 28, 1897 in the New York Times with the headline: “A Family Deserted for Her”. That article reported a bizarre act of vandalism near Mt Holly, New Jersey. The headline continued: “Fateful Statue Broken: Marble Effigy of Agnes Gilkerson Demolished by Orders of the Son of Hezekiah B. Smith”.

Why did this ‘son’, a man so enraged, want to destroy a statue dedicated to a woman who had died 26 years earlier? And who was this woman, so much despised and vilified by an article in the New York Times?

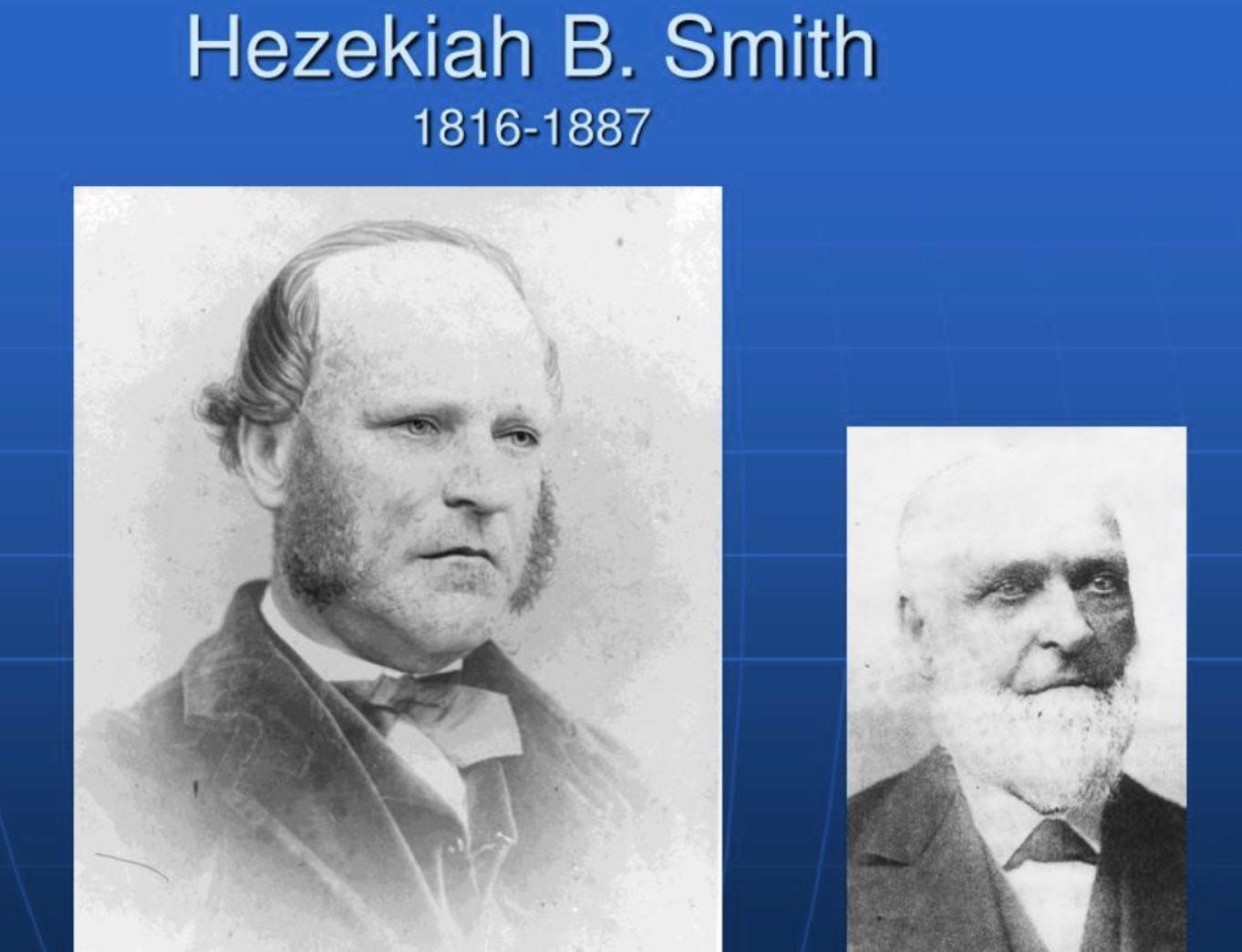

Our story begins in 1854, in Massachusetts, in the town of Lowell, just northwest of Boston. Lowell is most famous as the cradle of the American Industrial Revolution. Seven years before the outbreak of the Civil War, a 16-year old Agnes M. Gilkerson from Vermont took a job in a local textile factory and caught the eye of inventor Hezekiah Bradley (H.B.) Smith, also from Vermont.

A successful, self-taught cabinet maker and later woodworking machinery builder, H.B. was 24 years her senior. Coming from the same state, the two must have quickly felt an affinity for each other, and probably had many common acquaintances and experiences.

In need of a secretary, H.B. offered the job to the stunning and charming Agnes, who had grown up on a farm. In a page right out of Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (“My Fair Lady”), H. B. took the teenager under his wing, eventually paying for her college education in Philadelphia. In 1861, she graduated from Penn Medical University, with a major in Chemistry, and she became a doctor.

While H. B. cared for the teenage Agnes during the 1850s, there’s no evidence they had an intimate relationship at the time. She was in Philadelphia and he remained in Massachusetts. H. B. was father to four children, who lived with his common-law wife back in Vermont. Personal letters prove that H.B. sent money to his children and their mother, Ms Eveline English. The family had no financial worries.

“[Eveline] refused early in their marriage not to live with H. B. As far as divorcing [Eveline], he tried. He purchased a house for her, put the deed in her name and several hundred dollars in her bank account,” said Sherry Leinbach, a trustee of Friends of the Mansion at Smithville, as H.B.’s and Agnes’ estate is known today and which is open to the public as a museum.

(H. B. early in life, and later as a broken man)

In 1865, at the end of the Civil War, H. B. and Agnes (now Smith) were already a couple, the details of which are hazy; for example, it’s not fully clear if they ever were officially married. The situation in the small town of Lowell was apparently unbearable and they seem to have been forced to leave Massachusetts.

If you want privacy, far from prying neighbors, then what better way to do that than purchase your own town and making yourself its mayor. That’s exactly what Mr and Mrs Smith did. The couple purchased the entire village of Shreveville in south New Jersey for the vast sum of $20,000, renaming it Smithville.

Crucial in their decision was the fact that the village was close to a waterway and a rail line that led to Philadelphia, the second largest city in the country.

“His first order of business was to get the factories rebuilt and running, and his attention then turned to rebuilding many of the worker’s houses and adding additions to the mansion. Both he and Agnes were involved together in the decisions of remaking Smithville what it is today,” says Ms Leinbach.

Smithville became the home of their firm, the H. B. Smith Machine Company, which became one of the largest woodworking machine companies in the U.S. Official government documents of that era reported that Smith “is making money fast.”

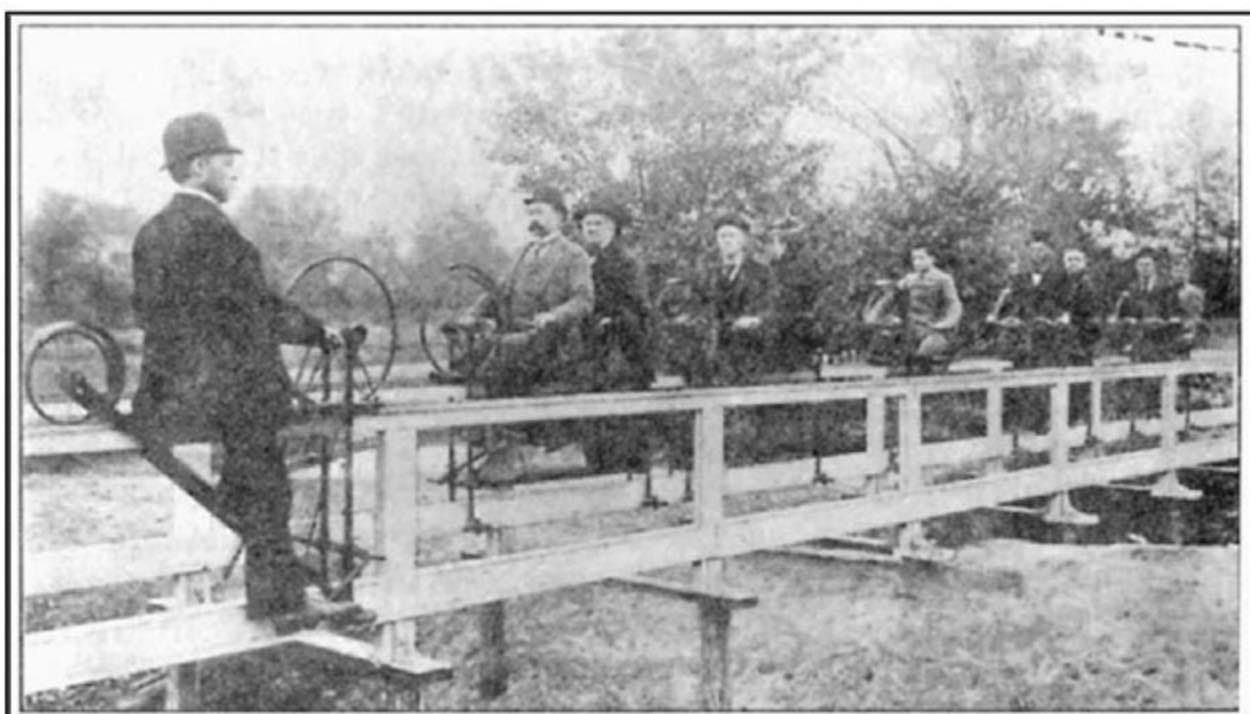

H.B. would eventually earn 40 patents for woodworking machinery, and in 1881 the company expanded and began to manufacture the American Star Bicycle, which became the popular racing bike of the day. He also made strange and innovative contraptions, such as a bike ‘path’ (below) that connected his estate with the nearby town, allowing workers easily and conveniently to get to work.

While H. B. was an engineering genius, Agnes had business savvy, especially a knack for sales and marketing. She also used her medical knowledge to launch new products.

“She put her expertise in chemistry to use in developing medicinal products, including ‘Madam Smith’s Celebrated Hair Restorer and Beautifier’. These products reportedly provided her with a considerable income,” added Ms Leinbach. Agnes was also the editor of the New Jersey Mechanic, a weekly publication.

By the standards of the time, and even today, H. B. and Agnes were an enlightened couple. They provided housing for workers and their families who were well-paid. The company didn’t exploit child labor, (as was common at the time), and instead, the workers’ children went to school for free. The town had an opera house, and dance performances were also held. Life was productive and fulfilling in Smithville.

By all accounts, H. B. and Agnes had a very warm and compatible relationship. Both had musical interests: he played the violin while she played the piano. Each afternoon after tea, they took walks and discussed each other’s day.

(Smith mansion seen from main entrance - my photo)

What had driven a successful and wealthy man, with four children, to pursue a young woman of no social standing, and to invest in educating her? Agnes clearly possessed natural grace, charm, wit and intelligence. One look at her photo makes that clear. More clues can be found in documents that came after their death. When their estate was to be decided by the courts, witness testimony left us an exceptional record.

One man described meeting Agnes in 1878: “She was one of the most elegant entertainers and the finest hostess I have ever met in my life; a lady of great ability; a fine conversationalist; a well-disposed looking lady; as fascinating a woman as I almost ever came in contact with.”

Another said: “[Agnes] was a woman I’d consider decidedly intellectual above the average; very brilliant in conversation, quite spicy, and altogether a very fine-looking and fascinating lady”.

Smithville’s happiness and idyll was not to be long, however. The tragic day came on Jan. 26, 1881. We are told that cancer was the cause of Agnes’ death. They had no children. H. B.’s diary reveals the depth of his despondency. Saturday, Jan. 29, 1881: “Prepared to attend the funeral of my wife.”

Sunday, Jan. 30: “A very sad day it was for me.” Monday, Jan. 31: “Feeling very lonesome and disconsolate. Do not expect any more happiness in this world. Have prepared myself for misery.”

(Smith Mansion seen from main road — my photo)

The 27-year relationship between H. B. and Agnes Smith is perhaps one of the greatest and most beautiful American love stories. However, beyond the walls of the Smithville museum estate that was once their home and work, the world has only heard a nasty, sensationalist and distorted version of their life together.

Where did such slander originate? Politics, as always. Hezekiah was also a state senator and later U.S. congressman from New Jersey. This meant he had enemies, who in turn had friends in the local and national media. Not surprisingly, those nasty accusations still persist 130 years later.

Fast forward to our modern era, to October 2014. Even though more than a century had passed, and more information was available, The Atlantic monthly ran an article with the headline: “Long-Dead Bigamist Congressman Still Haunts South Jersey”.

The author referred to “the ghastly true tale of Hezekiah Smith”, and the rest of the article focused on alleged hauntings in the mansion and grounds. There’s none of the beautiful details about their lives and love as I recount above. Bizarre.

(The statue of Agnes destroyed by Eveline’s and H.B.’s angry son)

“Many of the negative articles were of a political nature, H. B. was very active in politics, being a Congressman and a N.J. Senator,” said Ms Leinbach. “After H. B.’s death, and the start of lawsuits, the papers had a field day with writing many disparaging articles concerning Agnes and H. B.’s relationship. Elton Smith (H. B.’s oldest son) had a clear dislike for Agnes and was very angry with his father for the remarks he made during the bigamy scandal.”

Was H. B. a bigamist? Let’s look at the facts.

First of all, H. B. had a common-law marriage to Ms English, and since they had not been living together for almost two decades, it’s a far stretch of the imagination to consider the two to be “married”, even by the puritanical standards of the time.

In H. B.’s mind they were not married. But yes, he was a responsible and caring man, and maintained his financial obligations to the children and Ms English. Certainly she felt jilted, and the children grew up angry, mistakenly believing that Agnes had taken their father away. That’s understandable. But it’s time to set the record straight.

Perhaps the couple’s alleged haunting of the mansion and grounds owes to their memory having been unjustly sullied and disrespected. It’s high time we restore a sense of justice and fairness to the memory of Mr and Mrs Smith; that we turn our backs on the hate of their detractors, both past and present.

Let this Valentine’s Day, almost exactly 141 years since the day of Agnes’ death, mark the day when we celebrate their lives and love, and all that is Noble, True and Just.

ENDS